Lessons Learned from Wisconsin’s Pandemic Primary

By Shauntay Nelson and Emily Belle

On April 7, the world saw how some decisionmakers leveraged COVID-19 to threaten our democracy — and our lives. Because they failed to act, many Wisconsin voters were forced to make an unacceptable choice: their health or their right to vote.

We — a Wisconsin voting rights advocate and a Milwaukee-based lawyer — witnessed this failure of leadership firsthand. We were shocked by images from Milwaukee where predominantly Black and Brown voters waited in long lines, at times in hail, to cast their ballot — and all while the state was under a shelter-in-place order. That can’t happen again. As November approaches, and as epidemiologists warn of a surge in the virus this fall, Wisconsin officials must respond with an election plan that works for all voters, particularly those who have long faced barriers to the ballot, including African Americans, low-income voters, voters with disabilities, and students. The actions we take now will determine not just how we weather the virus, but also the kind of democracy we will have when it’s over.

What We Saw

Election officials were unprepared to run an election during a pandemic. Nearly 1.3 million Wisconsites requested absentee ballots. Decisionmakers blocked deadline extensions that would have provided more time to face that enormous challenge. Their lack of preparation coupled with these restrictive deadlines meant many voters failed to receive their ballots, complete them, and return them in time.

Decisionmakers also prevented necessary relief by tightening needless and discriminatory barriers like the witness signature requirement. In municipalities across the state, voters reported not being able to procure a witness signature because they were following our state’s safer-at-home order. Officials must remove this requirement immediately so that no voters — particularly young people, single parents, older adults, and those living alone — are disenfranchised.

Election Day was a debacle. Emily worked as an elections inspector at Marshall High School, one of only five polling places in Milwaukee, down from 180 in the last election. The school is situated in a predominantly Black neighborhood. Black and Brown communities have been hit the hardest by Wisconsin’s COVID-19 outbreak. Taking her temperature ahead of time, Emily arrived with a mask and chef’s coat to protect herself. She was glad to see the site equipped with masks, gloves, and sanitizer, but only a few people had access to the more protective surgical gowns.

Photo: Dora Drake of Milwaukee, Wisconsin

As Emily assisted with curbside voting, she noticed that some voters didn’t get the chance to vote — likely because of the two- to three-hour long wait as lines wrapped around multiple blocks. Additionally, because so many polling places in the area had been shut down with little notice, many voters showed up at the incorrect polling place. Emily had to inform voters — disproportionately Black voters who had waited for hours — that they needed to vote in a different location. For those who could take more time off work and head to a different polling site, many were not able to arrive before polling places closed at 8 p.m.

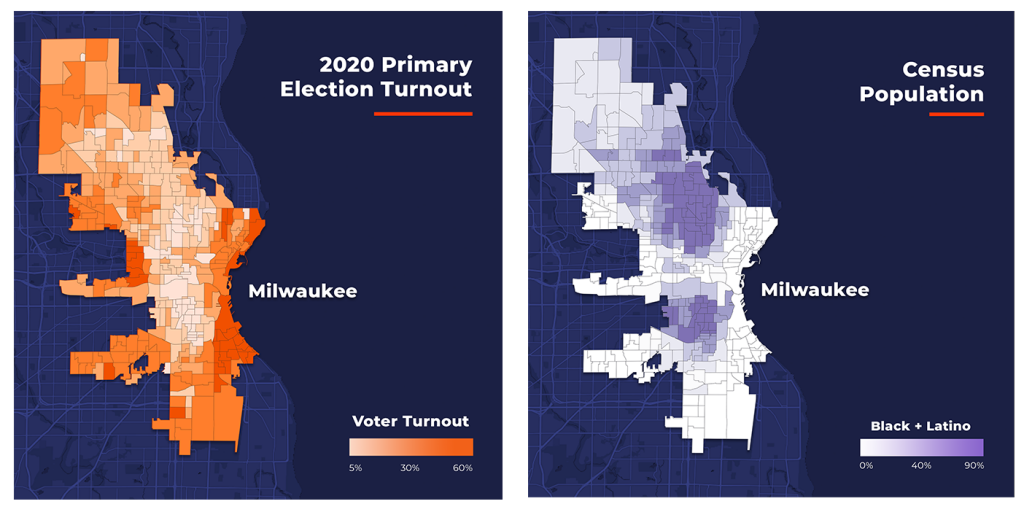

Like the emergency situation itself, the resulting disenfranchisement should alarm us all. Voter turnout in Milwaukee wards with higher Black and Hispanic populations was 30 percent lower than the average voter turnout in White wards, according to a new analysis from All Voting is Local and Demos.

What We Must Do

Officials can take simple steps to fix these problems. First, the state should mail all registered voters an absentee ballot at least 45 days ahead of an election, so elections officials don’t face the chaos of overwhelming requests. Second, lawmakers must eliminate the witness signature requirement for voting absentee. Third, lawmakers must permit absentee ballots to count if they are postmarked by Election Day. If ballot requests are delayed, voters will still be able to return their ballot, particularly if election officials expand options to return them.

Officials must also protect and expand safe, in-person early voting opportunities. In-person voting provides critical access for voters with disabilities, voters without internet access, voters who are experiencing homelessness, and voters who need language assistance. Decisionmakers must ensure that there are ample early voting and election day polling places based on population. Otherwise, communities of color could again be doubly impacted by both the virus and preventable barriers to the ballot.

Despite the challenges in Milwaukee, we were impressed by how many voters showed up. We heard voter after voter say, “They thought we weren’t going to come out, but we did.” Still, voters should never have to choose between their health and their right to vote. We need fair, safe, and accessible elections — for everyone. Though the April primary election presented unparalleled challenges, we know what needs to happen to ensure every Wisconsin voter can receive a ballot, cast that ballot, and have it counted — in August, November, and beyond.

Shauntay Nelson is the Wisconsin State Director with All Voting is Local. Emily Belle is a Milwaukee-based criminal defense lawyer. She has volunteered with local Election Protection efforts for more than 15 years.