Our Voices Matter: How Georgia’s 2020 Count Shaped Representation

By Imani Bryant

In March 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau mailed out millions of paper notices and questionnaires asking households to complete the decennial census. I arrived home from college for spring break, and what would then become COVID quarantine, and opened the mail — and just like I had a decade before when I was 10 years old, I filled out the census form for my family. Having learned in school the importance of the census, I completed these questionnaires for my family because I felt a sense of civic duty.

The 2020 Census was unlike any the country had ever experienced. It was plagued by uncertainty around an ultimately rejected citizenship question, low response rates, high undercounts, the rollout of a predominantly online format, and a once-in-a-century pandemic that permanently changed the world’s population. The 2020 Census also set the stage for controversies surrounding the 2022 midterm elections and the 2024 election.

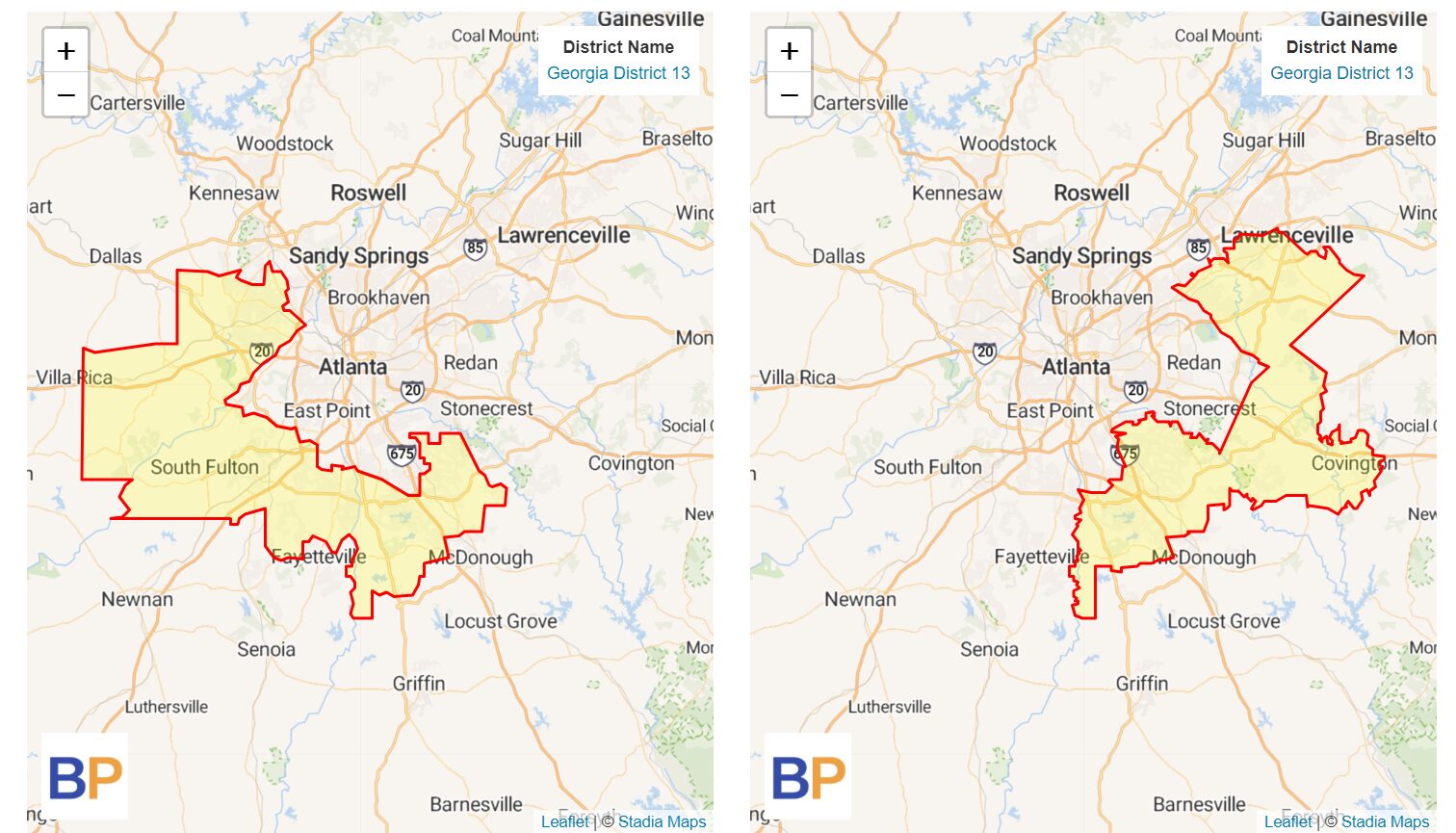

My state of Georgia is home to 10,711,908 people, according to the 2020 Census. Since the 2010 Census, we have had 14 congressional districts and 16 electoral votes. For most of my life, I lived in Georgia’s 13th congressional district, represented by David Scott since 2003. Since its creation after the 2000 Census, this suburban Atlanta district has been primarily composed of working-class Black and Brown families. Though the borders of the district have changed twice since then, GA-13 is one of the districts in Georgia’s “Black Belt,” which stretches from Augusta to southwestern Georgia and is home to a majority of the state’s Black population.

After the 2020 Census resulted in newly drawn districts, this area became the subject of several lawsuits challenging Georgia’s state legislative and congressional maps. These cases, including Common Cause v. Raffensperger, Pendergrass v. Raffensperger, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. v. Raffensperger, and Grant, et al. v. Raffensperger, accused the state of diluting the voting power of Black Georgians through racial gerrymandering in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). They argued that the newly drawn districts did not accurately represent the state’s growth in the last decade. Even with reported undercounts, the 2020 Census data show that the Black population grew by nearly half a million, and Black residents accounted for one-third of the total state population.

The initial proposed districts drew only four predominantly Black congressional districts. The federal district court struck down these plans in October 2023 as violating the VRA and gave the state until December 8, 2023 to enact remedial plans. On November 22, 2023, the state appealed the district court’s judgment to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, but it still proceeded to create remedial congressional and legislative plans before the court-imposed deadline. On December 28, 2023, the court approved the state’s new plan, leaving Georgia with five majority Black districts. However, the original plaintiffs are still awaiting an appeal to this decision due to ongoing concerns of racial discrimination even under the newly drawn districts.

While the case awaits resolution, the congressional maps for Georgia are currently set for the 2024 election cycle with the five majority Black districts. For the first time in my life, I will not be voting in Georgia’s 13th congressional district. My family’s polling place will not be the middle school where my dad has taught for more than a decade. Instead, I will be voting in Georgia’s 14th congressional district, which is composed of mostly rural white voters. The newly drawn district stretches from the northwestern Blue Ridge Mountain region to a sliver of southwestern Cobb County, which is part of the greater Atlanta metropolitan area and my hometown. Meanwhile, one street over from our home remains in the GA-13th district.

Maps of Georgia District 13 before and after 2020 redistricting cycle.

The census tells the story of the dynamic growth not only in my home state of Georgia, but also of the diverse communities across the nation. It provides a snapshot of each community every 10 years, which influences the political landscape of our nation for the following decade. By evaluating who lives in your area, the census is instrumental in determining where you vote, where your children go to school, and how much money and resources your community receives through government programs. This is only one small part of the story of the power the census holds, and it serves as the bedrock on which the entire process of federal and state redistricting and enumeration rests.

Imani Bryant is the senior campaigns and programs assistant for the census and data equity program at The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.